Whenever I think of Guru Dutt, I think of two of his films. No, they aren’t Pyaasa or Kaagaz Ke Phool. As much as I love them, and I do, deeply, and as lucky as I’ve been to watch them on the big screen in the last few years, they aren’t the ones I return to. Maybe because they leave me too undone. Maybe because they are too complete in themselves, too soul-stirring, too perfectly aching, and, sometimes, too personally haunting. So instead, I find myself thinking of two others. Indeed, not as cinematically accomplished, not as poetically distilled, perhaps not as even polished. But they are more revealing. Indeed, not the masterpieces that sealed his legacy. But they revealed who he was before he knew it fully himself. These are the films that tell me more about the artist becoming, rather than the artiste already arrived.

One of them is Mr. & Mrs. ’55, the film that changed everything for him. It was after that he became the Guru Dutt we speak of now, the one preserved in sighs and frames. But I’ll write about that some other day. Today, I want to write about the other one. The first one. The film that might, in some corners, be called his weakest, if only because what followed was so impossibly rich. But that’s the thing about Dutt: even at his most unfinished, his least certain, he is already more than most at their sharpest. After all, even in his fragments, there is force. And even in force, there is always a feeling. So Baazi it is.

Watching Baazi today, it might appear inferior to many. It’s a film full of turns we now call cliches. You can see the twists coming from a distance; even the smallest scenes feel like they’re announcing themselves in advance. But to view a historical work without its context is, frankly, an act of ignorance, and to do so with a Dutt film is something far worse. What looks like familiarity now was, in 1951, completely unexpected. The beats we now anticipate, they were all new once. And Baazi was among the first to strike them. Film scholars have often credited it as the film that lit the spark for the urban noir in Hindi cinema, a style and mood that would come to define much of the 1950s. So seminal was its form and feel that Raj Kapoor would do it in his own style with Shree 420 just four years later. Yes, Awaara, which came out the same year as Baazi, shares its own tonal kinship, and that’s a fair conversation to have, but Baazi remains the first of its kind.

And more than that, it was made by artists who themselves were at their beginning. Dutt, of course, started his innings with it, alongside Johnny Walker, whose first stint with comedy was in Baazi. There was lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi, whose first proper success was Baazi. Zohra Sehgal, who choreographed the songs, was still years away from becoming the iconic actor we remember her as, but post-Baazi, her skills were in some demand. Raj Khosla, still at least five years away from directing his blockbuster CID, began his career as an assistant on Baazi. And then there was V.K. Murthy (not yet the master of light and shadow that he would become, not yet Dutt’s visual muse), who worked here as a camera assistant, but still he left his stamp on both Dutt and the audience. In fact, one of my favourite shots from the film was also taken by him.

Also Read | Guru Dutt@100: How songs became the soul of his films

So, it’s in the song ‘Suno Gajar Kya Gaaye’, where the moll, Nina (Geeta Bali), warns the hero, Madan (Dev Anand), that he is going to be killed, through the words of Ludhianvi and a dance choreographed by Sehgal. While a lot of scholars, like Nasreen Munni Kabir, have written extensively about the ending of the song, where, through rapid cuts, Dutt builds tension and immerses the viewer. However, for me, the genius of Dutt as a director and Murthy as a cameraman lies in the opening of the song. It begins with Nina starting to dance, and we see her not directly, but through a mirror. Soon, the camera pans, and we see Madan walking into the club to take his seat. It’s not just a regular panning shot, it’s a dolly movement preceded by a tilt down, all done together with poetic grace.

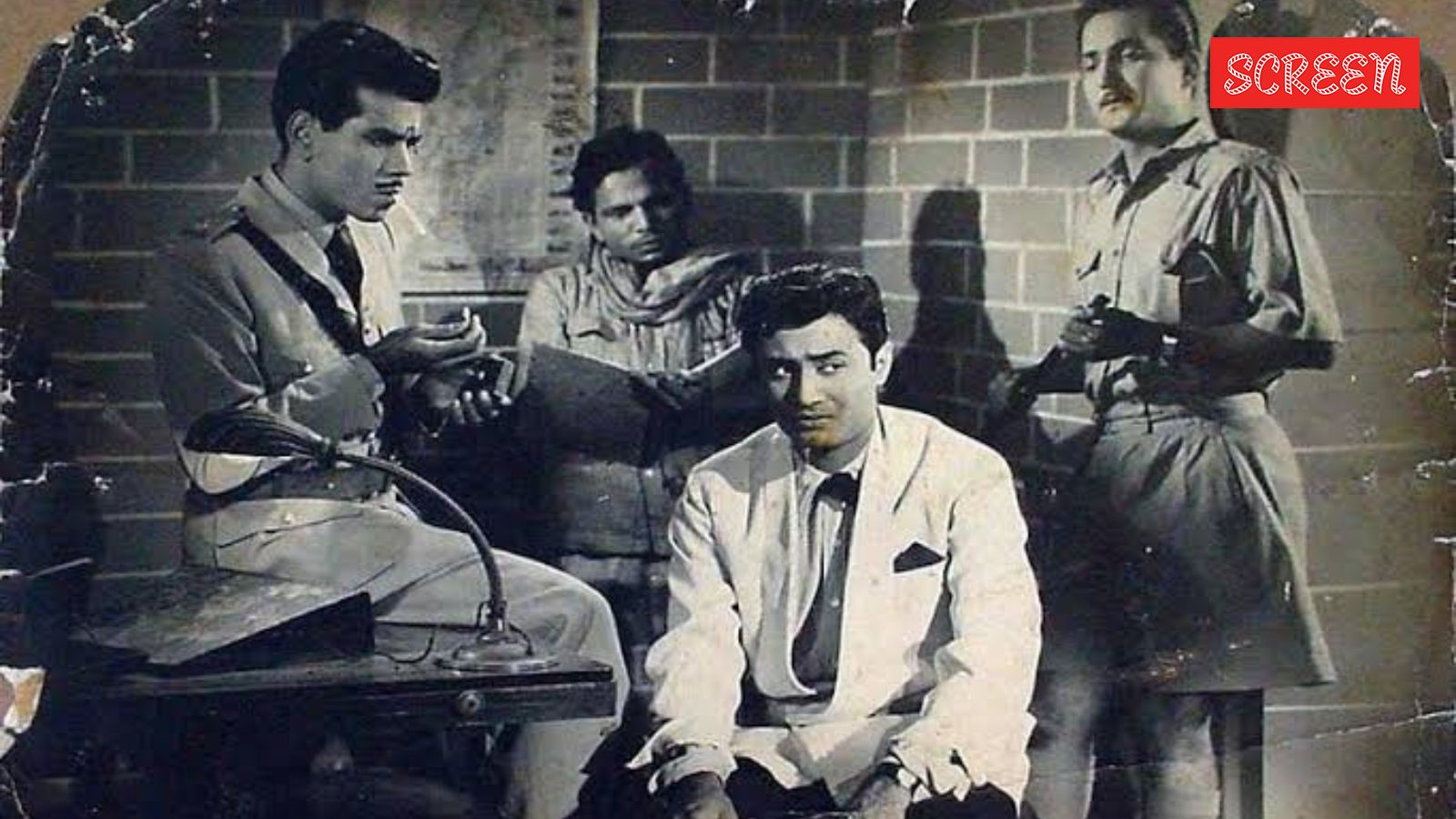

(Photo: Express Archives)

This is where Baazi peaks for me. In the way it understands the grammar of song picturisation, something no one before, or perhaps since, has grasped the way Dutt did. Almost every song in the film became a blueprint, a trope that continues to shape the language of storytelling in Bollywood even today. Take, for instance, the film’s opening song, ‘Sharmaye Kahe Ghabraye Kahe,’ where Nina tries to draw Madan into the club, and into a life of crime. It’s a moment that Kapoor would imitate, in his own way, with style and flair in ‘Mud Mud Ke Na Dekh’ from Shree 420. And then, of course, there’s the all-time great: ‘Tadbir Se Bigdi Hui Taqdeer’. A ghazal at heart, but one that S.D. Burman daringly sets to a hip, Western beat, as Nina attempts to seduce Madan. What stands out, again and again, is minimalism. Because that’s what Dutt understood, the art of withholding.

Story continues below this ad

There is no spectacle here. No sweeping camera movements, no elaborate sets, no frantic edits. Just the barest essentials, the camera held close, intimate, drawn towards both Bali and Anand. The tension isn’t in the choreography. It’s in the distance between two eyes, in the pause before a line, in the silence the music moves through. That’s the thing with Dutt, the quality that would later make him an artist impossible to ignore. The real story, the real tragedy, is never on the surface. It lives just beyond the obvious. His frames are so layered, that both the art and the artistry are never flaunted, but they are always present, hence always felt. And so it feels inevitable, almost poetic, that in his very first film, and in the very first shot of that film, we find him, as a nameless figure, sitting alone at the corner of a street, watching the world pass. The camera doesn’t lean in. It barely notices him. He could be anyone. A poet, at odds with the world, like Vijay from Pyaasa. Or a filmmaker broken by beauty and its cost, like Suresh from Kaagaz Ke Phool. Or maybe, simply, he is what he was. An artist, unknown to the world, waiting at the edge of the frame, for his taqdeer to unfold.